Capital, Colonialism, and the Breakdown of the Social in demonlover (2002) and Caché (2005)

The turn of the millennia saw the advent of an increasingly interconnected society. Through trends in globalisation that saw culture and commerce circulate across international networks at unprecedented rates. Moreover, where the prominence of communication technologies, epitomised by the growth of the internet, helped spur on this global exchange. Thus, in the age of mass interconnectivity, why do films from this period reflect the seemingly paradoxical anxiety of deteriorating social relations?

This essay will attempt to answer this question by offering close analysis into two films from the early-2000s: Olivier Assayas’s demonlover (2002) and Michael Haneke’s Caché (2005). This analysis will be done through a reading of social deterioration, defined in my own terms as the failure between interpersonal relations – between the subject and the Other. In doing so, this essay will uncover the convergent and divergent sources of social deterioration by traversing the sites between technology, capitalism, and postcolonialism within both films.

Before delving into the body of my analysis, I will briefly introduce the two texts. demonlover revolves around the corporate power struggle for hegemony over the international pornographic market, whereas Caché follows Georges, a bourgeois television presenter, as his life is continuously disrupted by the appearance of surveillance tapes that force him to confront both personal and national traumas.

The most overt point of comparison between these films is how both narratives are driven by politics of the image, seemingly taking adage from Guy Debord’s concept of the spectacle. Debord postulates how the ‘spectacle is both the result and goal of the dominant mode of production’, that all socioeconomic life dedicates itself to the image.1 Albeit Debord speaks prior to a time where mediatised technologies have the stronghold that they do within a post-internet society, nonetheless his statements can be viewed as remarkable precognition to the depiction of the present day posited by both films.

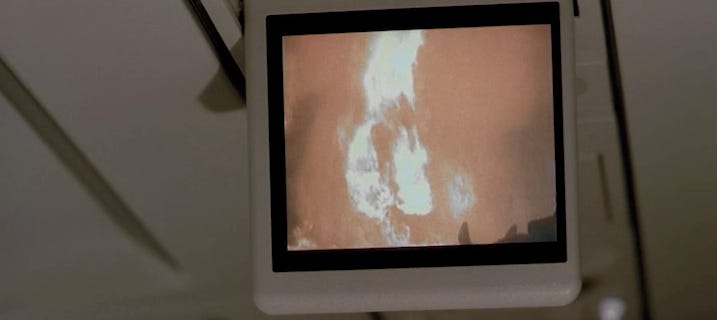

As a result, demonlover reflects the control the image holds over contemporary society. This is reflected within the opening shots, as explosive footage plays on the airplane’s televisions that is met with indifference by the passengers. Similarly, the incessant depiction of pornographic footage sprawled on television sets and computer screens are viewed with subdued gazes.

These examples not only showcase where the spectacle is being set as the dominant mode of production and consumption, but the apathy these images generate points towards a society that is so normalised to the proliferation of the spectacle that they find these images unremarkable. The result measures to Martine Beugnet’s reading that ‘transgression itself is but one facet of the trade strategies’ within the film, forced to satisfy an increasingly desensitised consumer base.2 This can be evidenced when audiences witness the Volf executives contemplate the marketability of computer-generated pornography that is predicated on extreme brutality. Elsewhere, the Hellfire Club promises an interactive torture experience on the internet which allows its consumers to enact violence whilst being removed from the vicinity of the victim. demonlover showcases a shift in consumer desires that directly showcases an erosion of the social sphere, whereby consuming and even partaking in acts of brutal violence is no longer taboo – empathy for the Other has withered away. At the same time, the pervasiveness of pornographic material leads Serge Kaganski to state ‘the more omnipresent sex is, […] the less these characters make love; their libidos have been drained.’3 Here, Kaganski suggests that the representations of sex are shown to be more gratifying to the protagonists than actual physical connection. This co-opting of mass violence and sexual imagery converge into the common effect of eroding intersubjective relations, either as a site where desire is displaced or where consumers become desensitised to the feeling of the Other.

Simultaneously, the proliferation of images could also be understood in relation to a Baudrillardian hyperreality, where representations ‘masks the absence of a basic reality.’4 In this case, the distinctions between the realm of images and reality become blurred as the real world begins to match the artifice of the image. In demonlover, this manifests through the transitory sites of airports, hotels, and vehicle interiors. These settings deny the characters any rootedness or spatial anchorage, denying them space to exhibit meaningful connection. This is further compounded by the postmodern architecture that characterises the corporate office blocks, distinguished by their transparent and reflexive surfaces.

These features add to the immaterial aesthetic of the film, as the characters themselves navigate a hall of mirrors that only further alienates them from their landscape. This alienation is also seen in the characters themselves, who display no psychological depth beyond their corporate lives. Diane, the film’s focal subject, is depicted solely through external shots, the camera careful never to pierce into her subjectivity as she drifts through the corporate realm. In this manner, she is also estranged from the audience, since they too, are denied any points of connection into her character. This feature became a major gripe with critics upon the film’s release, offering Todd McCarthy’s example:

As the film wears on, it becomes increasingly apparent — and increasingly detrimental to it — that Assayas never developed a sufficiently clear picture of this duplicitous and evil woman, what drives and obsesses her, and how she imagines she’s going to pull off the major subterfuge she undertakes.5

What McCarthy and other critics overlook is that her lack of interiority corresponds to the film’s own hyperreal aesthetics – Diane appearing as almost a representation of humanity itself. This is continued within the other characters in demonlover, whereby the absence of any personality leaves them to resemble the digital avatars that are proliferated through cyberspace. Thus, the symbiosis between space and subject in their shared artificial quality has a compounding effect. This depiction of reality not only mirrors the lack of depth seen in the representations that dominate contemporary society, but it also denies the social sphere the tangibility required in both subject and space to harness positive intersubjective relations.

However, Assayas’s stylised depiction of this vapid reality has invited critics to question his own ethical stance on the matter, offering the example of Kate Stables who writes:

‘The film seems half in love with the amoral jet-set criminals and ultra-transgressive internet eye-candy that it sets out to condemn, as if post-modern capitalism were just too damn shiny and pretty not to slaver over.’6

Stables references a clear sense of aestheticization towards demonlover’s proliferation of transgressive images and immoral corporate practises. This is best reflected in the muted and cool tones of Denis Lenoir’s cinematography which pairs mesmerizingly with the ambience of the Sonic Youth soundtrack. This entrancing atmosphere remains at odds with the deviousness of the narrative action. Elsewhere, the insistence of the various screens and graphics that intrude onto the frame showcases a clear reverence for the digital aesthetic. This includes the full exposure of pornographic footage which at times takes over the entire mise-en-scène, suggesting a problematic lack of distance taken by an apparent critique of modern society. In this manner, Assayas can be seen as conforming to the ideal of the spectacle, himself as proliferating the same images and representations of reality which erode the social sphere.

Haneke’s tempered and realist direction denies the hyperreal aesthetics that suit a Baudrillardian reading, yet the film still maintains an awareness of a society spellbound by the spectacle. This is evident through the incorporation of various television newsreels that proliferate images of conflict and violence from across the globe. However, these newsreels are often relegated to the backdrop of the mise-en-scène, often as distracting asides to the main action.

Thus, these images not only fail to sustain the attention of the protagonists but also of the audience as they are forced to manage their focus between the different emphasises within the frame. The fact that images depicting the suffering of others fail to arouse the full interest from both protagonists and audience, reveals the role they maintain in eroding the subject’s ability to empathise with another. Moreover, Ann Doane compounds this effect with her reading of non-stop television cycles as contributing to ‘the annihilation of memory, and consequently of history, in its continual stress upon the “nowness” of its own discourse.’7 The proliferation of the image is shown to introduce both disaffection to the Other while also denying the space for collective retrospection in social relations. Both consequences are manifest within a narrative focused on guilt and responsibility.

Unlike demonlover, Caché offers a mode of resistance to the proliferation of the spectacle. This is seen from the opening scene, as the initial establishing shot of a suburban neighbourhood extends to a three-minute run time that risks the audience’s disinvestment. The frame is absent of any narrative action and is only understood retrospectively in the following scenes as footage from a surveillance tape. As the narrative progresses, these tapes continue to punctuate the narrative, keeping with their distinct stillness and indifferent gaze.

These elements echo Debord’s own experimental cinema which sought to utilise anti-aesthetics to combat ‘the society of the spectacle’. In a society already established as complacent to the proliferation of the image, Haneke attempts to restore ethical viewing practises by reducing its aestheticized qualities. Hugh Manon describes this quality as ‘nonconfirmation’, that the absence of answers surrounding the tapes’ origin and purpose invites active interpretation from its spectators.8 For Georges, this quest of interpretation leads him to meet with the previously excluded Other, Majid, in the hopes of repairing previously fractured social bonds.

Both films undoubtedly view the proliferation of images and spectacle as reducing the collective capacity for authentic connection in a world that is increasingly impacted by the rise of communication technologies. The erosion of empathy, the displacement of real-world connection, and the inability for retrospection are seen as some of the negative repercussions stemming from this situation. Yet, where demonlover seems immobilised and perhaps entranced by these developments, Caché offers a mode of resistance through the denial of aesthetics that serve to deconstruct the allure of the image.

The rise of communication technologies was not the sole concern shared by both films regarding the decay of intersubjective relations. As aforementioned, the advent of the 2000s witnessed the intensification of global capitalism, reflected in the expansion of international trade networks and echoed in thinkers such as Francis Fukuyama. Concurrently, the 9/11 attacks not only acted in symbolic defiance of these systems of global capital but also reignited racialised divisions – most notably through the US-led War on Terror which was predicated on imperial logic and processes of racialised othering. Both Caché and demonlover engage with these contexts in differing ways to explore why the social sphere was under the process of deterioration. Demonlover posits its critique in the structures of late capitalism, whereas Caché focuses on the revival of postcolonial tensions. As Jennifer Burris argues, Caché treats Algeria as ‘a cipher through which to critique the manufacture of paranoia for political ends in post-9/11 neocolonialist ideology.’9 Despite their different emphases, both films showcase how social deterioration is dependent on systems of exclusion and domination. In this manner, the structures of postcolonialism and late-stage capitalism can be seen to mirror each other by producing realities where authentic relations with the Other become impossible.

Caché explores postcolonial relations primarily through its evocation of France’s colonial past, particularly through its dark history with Algeria. As Mohit Chandna writes:

[The film] displays how the bloodshed related to the Algerian war of independence, fought elsewhere and in another time, continues to rend everyday life right here and right now in the very heart of the French republic.10

Chandna reflects on how historical colonial violence maintains influence within French contemporary society. However, reducing Caché to solely a nationalist allegory overlooks its broader postcolonial implications. Haneke affirms this claim, stating that: ‘This film was made in France, but I could have shot it with very few adjustments within an Austrian – or I’m sure an American – context.’11 Thus, what should be prioritised is not the nationalist arena of conflict, but rather how the film seeks to critique exclusionary and hegemonic forces of postcolonial violence. In line with this, the examples of Georges’ conflicts with Majid, Majid’s son, or even the cyclist, are imbued with the influence of postcolonial dynamics as they all showcase Georges’ inability to reconcile with the racialised Other. This can be seen with his continued deflection of responsibility within these scenes, or in his hostile and aggressive tone.

Chandna’s reading supplies backdrop to these conflicts as they exemplify the persistence of historical racialised violence. Conversely, the dinner party’s inclusion of the token black friend does not speak towards the vilification of racial difference but rather an exoticisation of it – another form of racialised othering. These scenes showcase where racialised divides are always exacerbated by the barriers of postcolonialism, where difference cannot be met with sincerity and are instead plagued with ulterior dynamics.

This is further evidenced at the level of the film’s form, where subjectivity is privileged only to the white and bourgeois protagonist, Georges. This is enacted by aligning his character with the perspective of the audience, relegating the perspective of the racialised Other to the back of the audience’s mind. This touches upon the critiques Paul Gilroy had when reviewing the film, stating:

When the Majids of this world are allowed to develop into deeper, rounded characters endowed with all the psychological gravity and complexity that is taken for granted in ciphers like Georges, we will know that substantive progress has been made towards breaking the white, bourgeois monopoly on dramatizing the stresses of lived experience in this modernity.12

Gilroy is undoubtedly correct in lambasting the trend of the privileged white, upper-class perspective within cinema, albeit he perhaps misses Caché’s intentional usage of this technique. Majid’s denial of any subjectivity through the film’s formal techniques is a process that operates invisibly to its audience until the moment of his self-annihilation. This shocking scene forces confrontation with the audience’s collective ‘realisation to the extent to which [they] have underestimated and misunderstood his character.’13 By forcing audiences to reflect onto the narrative, audiences can understand where Caché’s alignment with Georges’s perspective has denied them access into Majid’s inner world. Thus, the film utilises formal techniques to replicate the exclusionary structures that castigates racialised difference.

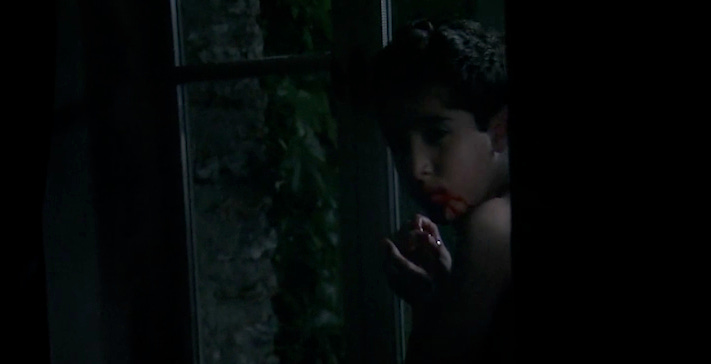

Caché also reveals the structures of racialised conflict to run deep, taking the example of when Georges and Majid were kids. Georges’ confession of lying to his parents about Majid’s condition to get him kicked out of their home resonates with the exclusionary politics of racism. Furthermore, Georges’ own foundational memories are saturated with the antagonistic reconstructions of a young Majid, depicting unnerving shots of his face bloodied or yielding an axe. When these images are later contextualised, they not only reveal Majid to be a victim of Georges’ cruelty but also reveal where the perception of the Other can be manipulated and vilified to serve a baseless antagonism.

Thus, not only do the structures of postcolonial violence influence its subjects from a young age, but they persist in the subject’s own psyche – allowing its exclusionary logic to live on and serve as detrimental to intersubjective relations.

The politics of exclusion and domination continues in demonlover, albeit they are influenced instead by the competitive logic of capitalism. This is established from the opening sequence as Diane is seen poisoning the drink of her fellow business associate. This is later revealed as a ploy to assume her victim’s senior role within the company, showcasing where the capitalist ideals of competition hang over this inaugural act of violence. Elsewhere, when Diane gets caught copying Elaine’s computer files, what ensues is a brawl that serves as microcosmic for the corporate battle between the two conglomerates that they represent. Its resolution can only be thought in the annihilation of the Other, much akin to the hegemonic market practises of monopolisation. These examples showcase where capitalism invites its subjects to turn on one another, where the games of domination fragment social ties.

In the realm of character, Jonathan Romney labels demonlover’s protagonists as ‘blank interchangeable pawns’, referencing their capacity to assume differing roles and positions of power akin to the logic of the market.14 For example, audiences view the characters of Diane, Hervé, and Elise, all interchange seamlessly to occupy varying levels of power over another. From Elise, who turns from secretary to administrating the Hellfire project; Hervé who goes from Volf executive to espionage agent; or Diane who becomes corporate double-agent into hapless commodity.

As previously mentioned, their lack of depth outside their corporate lives showcase that these characters are defined solely through their position within the capitalist power structure – a structure that enforces competition and erodes the sphere of the social. Furthermore, capitalism also serves to exacerbate the effects of preexisting inequalities – particularly of gender relations. For example, Hervé’s act of sexual violence not only evokes the disparities in gendered power but also reveals how this intersects with capitalism as he renders Diane as mere commodity. Her sole response in a system that emphasises her gendered subjugation is to meet violence with violence, as she shoots Hervé in the head. The penultimate sequence also showcases this intersection between gender relations and capitalism as it depicts Diane’s attempt of escape from the isolated site of the Hellfire Club. As she tries to escape her own commodification, she is forced into committing acts of violence with the various groups of men who imprison her. These examples showcase where capitalist structures impose over intersubjective relations by enforcing its ideals of competition and individualism in the face of the Other.

This essay has shown that both demonlover and Caché exhibit an undeniable anxiety regarding the condition of social relations within a twenty-first century society. Across both films, a shared diagnosis of social deterioration emerges through the proliferation of images and spectacle. This has been reflected by depicting the displacement of real-world sites of connection or in the widespread erosion of empathy towards the Other. Where Caché and demonlover do diverge in their reasonings for social malaise, their critiques of either postcolonial relations or late-stage capitalism mirror another as both structures not only exist as sites of exclusion, hierarchy, and privilege, but they also arrive at the same conclusions of leading towards fragmenting interpersonal relations.

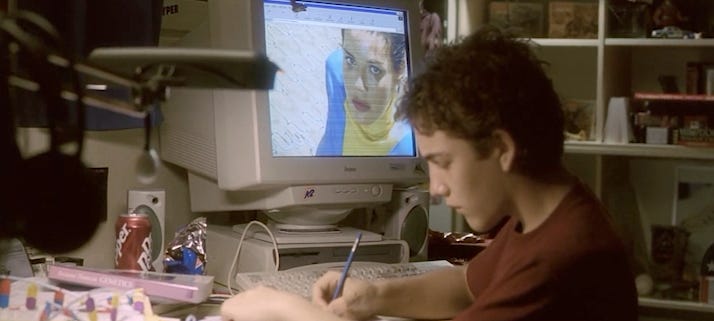

Thus, as both films align in their depiction of a corroding social sphere, they offer differing sentiments towards this process which is best articulated through analysing their respective endings. Demonlover’s final scene depicts Diane relegated to pure digitalised commodity as her gaze fails to illicit response from her teenage consumer. The cynicism of this ending reflects demonlover’s own paralysis with the effects of social deterioration, failing to envision a reality outside of intersubjective breakdown. This is markedly different from Caché’s optimistic depiction of progress as the scene showcases both Georges’s and Majid’s sons engrossed in conversation.

As such, the younger generation act as a symbol of hope in breaking down the historical structures that previously sought to divide them. In doing so, each film offers a contrasting picture for the future of social relations, one condemned to fracture and the other cautiously hopeful.

- Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle, (London: Rebel Press, 1994) p. 8 ↩︎

- Martine Beugnet, Cinema and Sensation: French Film and the Art of Transgression (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2007) p. 165 ↩︎

- Serge Kaganski, ‘Corporate Vampires, Bloody Catfights, Global Cyber Spy-Games: Welcome to Olivier Assayas’s Desert of the Real’, Film Comment, 39.5 (2003), 22-23, p. 23 ↩︎

- Jean Baudrillard, Simulations (Semiotexte, 1983) p. 11 ↩︎

- Todd McCarthy, ‘Demonlover’, Variety, 2002 https://variety.com/2002/film/markets-festivals/demonlover-1200549570/ [accessed 27/04/2025] ↩︎

- Kate Stables, ‘Demonlover’, Sight and Sound, 14.5 (2004), 52-53, p. 53 ↩︎

- Ann Doane, ‘Information, Crisis, Catastrophe’ in Patricia Mellencamp (ed.), Logics of Television: Essays in Cultural Criticism (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1990), 222-239 (p. 227) ↩︎

- Hugh S. Manon, ‘Comment ça, rien? Screening the Gaze in Caché’, in Brian Price and John David Rhodes, On Michael Haneke (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010), 105– 25. (p. 116) ↩︎

- Jennifer Burris ‘Surveillance and the indifferent gaze in Michael Haneke’s Caché’, Studies in French Cinema, 11.2, 2011, 151-163 (p. 160) ↩︎

- Mohit Chandna, ‘Caché, Colonial Psychosis and the Algerian War’ Interventions, 23.5 (2021), 772-89 (pp. 775-776) ↩︎

- Richard Porton, ‘Collective Guilt and Individual Responsibility: An Interview with Michael Haneke’, Cineaste, 31.1 (2005), 50-51 (p. 50) ↩︎

- Paul Gilroy, ‘Shooting Crabs in a Barrel’, Screen, 48.2 (2007), 233–235. (p. 234) ↩︎

- Maria Flood, ‘Brutal Visibility: Framing Majid’s Suicide in Michael Haneke’s Caché (2005)’, Nottingham French Studies, 56.1 (2017), 82–97 (p. 95) ↩︎

- Jonathan Romney, ‘Stop Making Sense’, Sight and Sound, 14.5 (2004), 28-31 (p. 30) ↩︎